Lyme nephritis: State of the Art Review | VETgirl Veterinary Continuing Education Podcasts

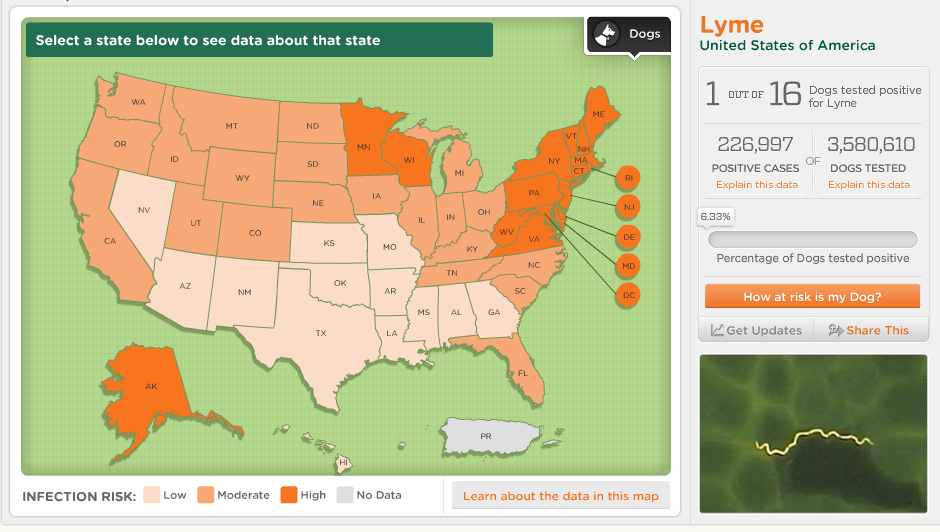

If you’ve practiced where VETgirl has, you’d hate Lyme disease as much as we do. Having practiced in all the tick-infested states (e.g., NJ, NY, MA, MN, PA, etc.), I’ve seen a lot of Lyme disease. That said, only a small subset of Lyme positive dogs (1-2%) go onto develop severe, life-threatening complications from Lyme disease – the dreaded Lyme nephritis. So, in today’s VETgirl online veterinary continuing education podcast, we’ll discuss this rare complication: Lyme nephritis.

In a State of the Art Review published by the Journal of Veterinary Emergency Critical Care in 2013, Dr. Meryl Littman from University of Pennsylvania reviewed Lyme nephritis, a condition resulting in protein-losing nephropathy (PLN). For those veterinary professionals practicing in the top 13 Lyme states, we are all too familiar with this devastating disease, along with all the complications associated with the pathogenesis including renal failure, cavitary effusion, thromboembolism and hypertension. For more information on Lyme disease, check out our other VETgirl online veterinary continuing education podcasts here.

Information obtained from CAPC at https://www.capcvet.org/parasite-prevalence-maps

Borrelia burgdorferi, the tick-born agent associated with Lyme disease, is an extracellular, motile, micro-aerophilic, gram negative, unicellular spirochete. While it is very rare for Lyme nephritis to develop in dogs, Golden and Labrador retrievers appear to be overrepresented. In a study published by Littman et al in 2006, more than 80% of retrievers diagnosed with PLN were also positive for Borreliosis. Based on the available date, a previous history of lameness has been reported in up to 28% of the cases. For more information, see the free, downloadable ACVIM Consensus Statement on Lyme disease.

Currently, the exact pathogenesis of Lyme nephritis remains unknown. Lyme nephritis results in Type 1 membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis (MPGN), characterized by diffuse tubular necrosis and lymphocytic plasmacytic interstitial nephritis. Immune complexes and positively charged antigens deposit in the subendothelium of the glomeruli, promoting an immune response and complement activation. Very few Borrelia organisms or DNA are found in the renal tubular cell on histopathology.

While Lyme disease can be experimentally induced in dogs, Lyme nephritis has not been experimentally induced, making it a harder disease to study. In an experimental group of dogs, a group of adult beagle dogs showed no signs of disease for more than one year after infection despite all having positive Lyme tests. Puppies between 6-12 weeks old showed mild self-limiting signs of disease somewhere between 2-5 months, typically in the limb closest to where the ticks were attached experimentally. All individuals in this study became carriers of Lyme, but no evidence of renal injury or PLN was reported.

Clinically, Lyme nephritis can result in the following presentation:

- Renal failure (e.g., PU/PD, uremic halitosis, weight loss, oliguria, anuria, vomiting, dehydration, etc.)

- Gastrointestinal signs (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, hypersalivation, melena)

- Hypertension

• Spontaneous bleeding (epistaxis)

• Sudden blindness (retinal injury)

• Acute CNS dysfunction (CNS hemorrhage) - Coagulopathy (e.g., thromboembolism)

- Respiratory distress (e.g., PTE)

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Acute central nervous system dysfunction

- Pleural/ pericardial/ peritoneal/ peripheral edema

- Exercise intolerance

So how do we diagnosis Lyme nephritis? Currently there is no commercially available test specifically for Lyme nephritis – just Lyme disease. We make the diagnosis based on the presence of proteinuria, an elevated UPC, clinical signs, history, at-risk breeds, and being seropositive for Lyme disease. Confirmation based on renal biopsy (which we’ll discuss later) is important, but is less commonly clinically performed.

Again, the majority of dogs with high B. burgdorferi titers do not suffer from PLN or other clinical signs (Again, it’s estimated that < 1-2% of dogs that are seropositive for Lyme disease go on to develop Lyme nephritis). That’s likely because Lyme disease is over-diagnosed as a result of diagnostic testing in seroprevalent regions (e.g., those 13 states!).

Some of the common ways of testing for Lyme disease include:

- SNAP 3DX, 4Dx & SNAP 4Dx Plus (Idexx): An in-house qualitative test that detects antibodies for the recombinant protein C6 after natural exposure occurs. A positive test can be obtained before lameness is noticed, approximately 3 weeks or more after acquiring the spirochete. Keep in mind that this test is very accurate, and that you don’t get a positive test from the Lyme vaccine.

- Lyme Quant C6: This is a qualitative test providing actual levels of antibodies against recombinant protein C6.

- Multiplex (Cornell University): This is a Western blot and provides quantification of antibodies against other Lyme antigens including OspA, OspC and OspF. Unfortunately, depending on what type of vaccine you are using, it does not differentiate between natural exposure and vaccine-induced antibodies as half of the Lyme vaccines available today contain the antigen OspA and C.

- Accuplex4 (Antech Diagnostics): Per the company, they claim that it can detect antibodies on an average of 1-2 weeks earlier than other tests, and differentiate individuals between natural and vaccine seropositivity.

Again, keep in mind that the incidence of seropositive dogs in your area will depend on prevalence. A positive test does not necessarily mean that the dog will develop clinical signs of Lyme disease, and may not necessitate treatment. A tentative diagnosis of Lyme disease is commonly achieved based on the clinicopathological presentation in endemic areas in seropositive dogs. Other causes of PLN must be ruled out (e.g., immune-mediated vs. non-immune mediated causes of glomerulonephritis).

Ideally, renal biopsies should be performed early in the course of disease to best identify the underlying cause. Renal biopsies are safe to perform, and provide meaningful and therapeutically helpful information when done early in the course of disease. Lyme nephritis is characterized by a membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis, and there are other causes of glomerulonephritis (e.g., non-immune-mediated), so it’s important to identify the appropriate cause to aid in appropriate treatment. Contraindications for renal biopsies include thrombocytopenia, hypertension and coagulopathies. Often antithrombotic agents (e.g., aspirin, etc.) are discontinued for a short period of time (e.g., 3-5 days) before the procedure. The ideal place to have these biopsies processed is at the Texas Veterinary Renal Pathology Service. Coordination with this center is advised before samples are collected.

When it comes to treatment for Lyme nephritis, a consensus statement specifically looking at the treatment of Lyme nephritis has not been achieved. Lyme positive dogs should be evaluated for proteinuria. Ideally a Lyme Quantitative C6 is performed pre- and post-treatment in these Lyme + dogs with proteinuria. Treatment is advised for those Lyme + dogs with proteinuria and should include appropriate antimicrobial therapy (e.g., doxycycline). Many dogs will continue to show positive results in qualitative and quantitative testing, regardless if they are treated or not. Seronegativity should not be expected as the goal of therapy. But quantitative Lyme C6 levels can be used as a therapeutic guideline. A 6 month-post therapy quantitative Lyme C6 reduction of 50% may warrant discontinuation of antibiotics.

Aggressive therapy is advised early in the disease process in dogs diagnosed with Lyme disease, PLN and kidney injury. Treatment of dehydration and hypovolemia is controversial. Those patients with severe azotemia and dehydration carry a lower prognosis. SQ route is preferred in those dogs that are mildly to moderately dehydrated; that are eating and drinking; and when there are no increased fluid losses in vomitus or diarrhea.

Complications associated with intravenous fluid therapy:

- Worsening of protein loss, hypoalbuminemia and decreased oncotic pressure can exacerbate edema, fluid accumulation and increase the risk of thromboembolic complications.

- Artificial colloid therapy (e.g., Hetastarch, Vetstarch, others) is commonly a choice of clinicians for patients with low protein levels and effusive conditions. Complications associated with these fluid choices include coagulopathies; iatrogenic fluid overload; hypertension; and acute kidney injury.

- Fluid overload and oliguria are commonly treated with diuretics. Hemodialysis and renal replacement therapy is indicated in those dogs that develop oliguria/anuria, persistent hyperkalemia and fluid overload not responsive to diuretics.

- In oliguric or anuric patients, the use of a diuretic may be necessary (e.g., furosemide 5-20mg/kg IV/ IM/PO TID- SID). If a response to furosemide is noticed (e.g., increased urine output), a constant rate infusion may provide better results than pulse therapy.

- Spironolactone 1-2mg/kg PO BID may provide additional diuresis for the management of effusions.

- Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors (enalapril 0.2-1mg/kg Q12- 24hrs; up to 5mg/kg PO SID, benazepril -0.2-1mg/kg PO SID, captopril 0.5-2mg/kg PO TID-BID) may help by decreasing proteinuria due to its effects in the afferent and efferent renal arterioles.

- Antiotensin-II receptor antagonists: Drugs like losartan can be used when patients are unresponsive to ACE inhibitors. The dose of losartan ranges from 0.125-0.25mg/kg (azotemic) to 0.5-1mg/kg/day (non-azotemic dogs).

- Amlodipine (0.1-.25mg/kg PO SID) is a commonly used calcium channel blocker, anti-hypertensive medication. Personally, VETgirl doesn’t think this one works well in dogs and prefers hydralazine instead.

Once the renal biopsy confirms the presence of immune complex deposition, immunosuppressant therapy is advised. Immunosuppressive therapy could be empirically initiated based on the clinical suspicion of immune-mediated protein losing renal disease, in those patient that are not good candidates for renal biopsy or those situations where finances may not allow for the procedure. The ideal therapeutic regimen is unclear at this point and what works for one patient may not work for others.

- Methylprednisolone sodium succinate 5mg/kg IV SID x 48hrs, followed by prednisolone 2mg/kg/d

- Azathioprine 2mg/kg PO SID x 2weeks; then 2mg/kg Q2days

- Chlorambucil 0.2mg/kg PO SID to Q2days

- Mycophenolate 10-20mg/kg IV or PO

With Lyme nephritis, immunosuppressive therapy is typically continued for several months before attempting to wean the patient off them. Side effects of steroids include gastrointestinal disturbances (e.g., ulceration); muscle weakness; hypertension; PU/PD; hypercoagulable states; and polyphagia. Azathioprine may increase the risk of pancreatitis and gastrointestinal disturbances. Mycophenolate can result in gastrointestinal signs (e.g., vomiting, diarrhea), bone marrow suppression and increased risk of infection.

In those animals that survive, the author of this study recommend rechecking urinalysis and bloodwork every 1-2 weeks. This depends on a case-by-case basis, as sicker dogs may need to be evaluated more often or those that are responding well to therapy could be evaluated less often as treatment and monitoring can be costly. Urinary protein losses are monitored via sequential urinary protein: creatinine ratios. Ideally, a urine sample is collected daily for 3 days. A small aliquot of these samples can be pooled together and submitted for analysis.

So, how do we prevent Lyme disease and Lyme nephritis? Lyme nephritis can be prevented by preventing the infection of ticks that harbor B. burdogferi. Very few dogs that are carriers of Borrelia do develop clinical signs of lamenss and even fewer of those develop Lyme nephritis. Tick repellant products are recommended as well as products that kill the ticks after attachment. Ideally, a fast acting tick kill is imperative (e.g., killing in < 4-8 hours) to minimize the risk of transmission of Lyme disease (e.g., Bravecto, Nexgard, etc.).

Overall, this state of the art review was a well written summary by a well know authority in the subject describing the data available regarding Lyme nephritis, and describes the clinical significance of the available tests and institutions that perform them without a bias. We know it’s frustrating, but not even the top authorities have figured out the pathogenesis and pathophysiology of Lyme nephritis! In the mean time, prevention, prevention, prevention.

References:

1. Littman, MP. Lyme nephritis. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2013; 23(2): pages 163–173.

2. Littman MP, Giger U, Nolan TJ: Seroprevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi antibodies in dogs at a veterinary teaching hospital in a Lyme endemic area. J Vet Intern Med 2006;20(3):761-2.

3. Boothe, DM. Small Animal zclinical Pharmacology 2nd ed. 2012 Elsevier, St. Louis

4. Greene; Infectious diseases of the dog and cat; 3rd ed.2006 Saunders, St. Louis.

Abbreviations:

MPGN: membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis

Only VETgirl members can leave comments. Sign In or Join VETgirl now!