November 2023

Emergency Room Approach to Anemia: Part 2 with Dr. Garret Pachtinger

By Dr. Garret Pachtinger, VMD, DACVECC, Director of Operations / Co-Founder, VETgirl

In Part 2 of this two-part VETgirl online veterinary continuing education blog, Dr. Garret Pachtinger, DACVECC discusses the approach to anemia in dogs and cats. Please make sure to read Part I HERE first to get your anemia knowledge on! There, we start with defining the types, causes, and diagnostic approach to the small animal patient with anemia!

Hemolysis: IMHA

Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) occurs when red blood cells (RBC) are coated with immunoglobulin, complement, or both, and are removed from circulation by direct destruction or phagocytosis. Destruction can be extravascular or intravascular resulting in a marked anemia and illness. Extravascular destruction occurs in the liver or spleen whereas intravascular hemolysis occurs when red blood cells are destroyed within the vascular system. Moreover, IMHA can be either primary or secondary in origin. Primary IMHA has no detectable cause for the presence of antibodies on the surface of the RBC and deemed an idiopathic disorder. Secondary IMHA occurs when antibodies develop on the RBC due to underlying causes such as infectious organisms (i.e., Lyme, Ehrlichia, Rickettsia, Babesia, Mycoplasma, viral, bacterial, etc.), drug induced (i.e., sulfonamides, methimazole), vaccine induced, toxins (i.e., garlic, zinc, onion) or neoplastic (i.e., lymphosarcoma, leukemia, etc.).

Clinical Presentation

Female dogs are more likely to be diagnosed with IMHA than male dogs. While this condition is uncommon in cats, male cats appear to be more likely to develop IMHA. Most dogs presenting with IMHA are middle age, with an average age of 6.5 years. While again uncommon in cats, cats seem to be younger when diagnosed with IMHA, an average of 3 years of age. The most common breeds affected by IMHA include Cocker spaniels, Miniature schnauzers, Poodles, English Springer spaniels, Collies, and Old English sheep dogs. Common owner complaints include lethargy, anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, pigmenturia, pale gums, and dyspnea. IMHA can also be associated with a seasonal presentation, with 40% of cases presenting between summer months (May / June). A thorough history should be obtained from the owner, including current and past medications (both prescription and over the counter), recent vaccinations, travel history, and previous therapies such as blood transfusions.

Physical Examination

Common physical examination findings include pale or icteric mucous membranes, a prolonged capillary refill time, snappy femoral pulses, tachycardia, and cranial organomegaly. It is important to perform a complete physical examination as examination findings may be similar to hypovolemia with examination findings including tachycardia and tachypnea and bounding pulses. Cranial organomegaly (hepatosplenomegaly), fever, and lymphadenopathy may also be present.

Clinicopathologic Findings

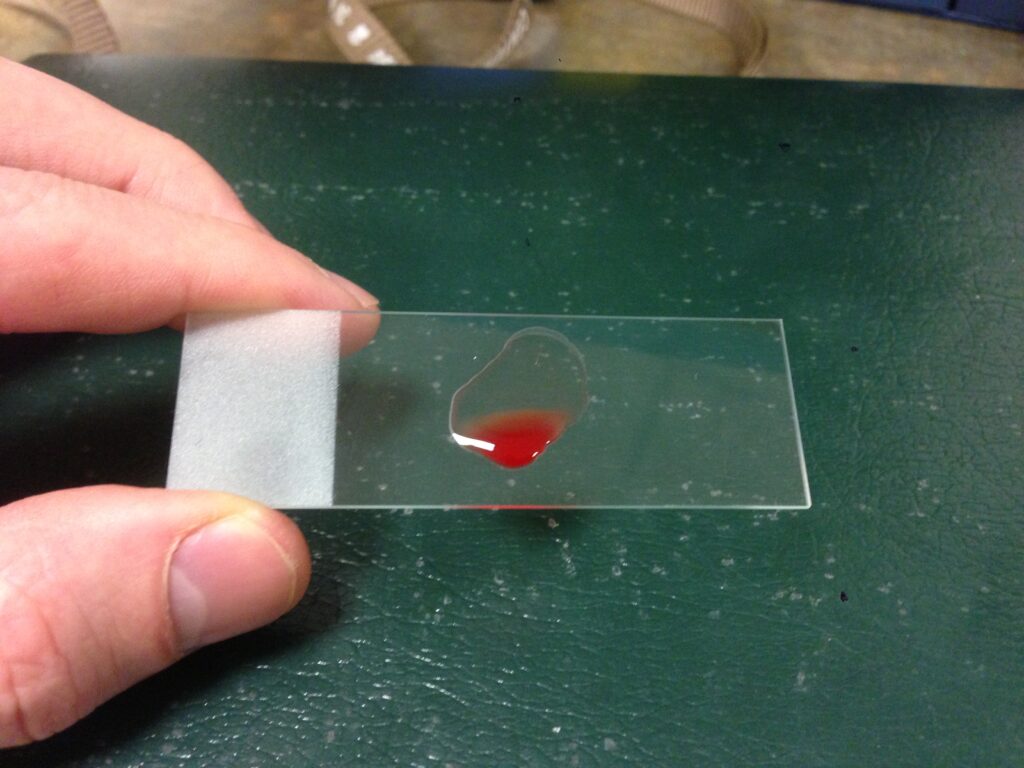

The minimum database (MBD) can be incredibly helpful in making a rapid, and cheap diagnosis in the busy emergency room. The MBD includes the PCV (packed cell volume), TP (total protein), Azo (Azo stick®), and BG (blood glucose). These rapid, cheap, and readily available tests provide clinically useful information in a short period of time. Added to the MBD, if there is evidence of anemia and icterus, a drop or two of blood can be saved for a slide agglutination test and blood smear. To perform a slide agglutination test, the clinician adds one drop of fresh blood with one drop of 0.9% saline and gently mixes them together on a glass slide. The clinician observes the slide grossly for the presence of agglutination and also microscopically, not only to confirm this finding but to distinguish this from rouleaux.

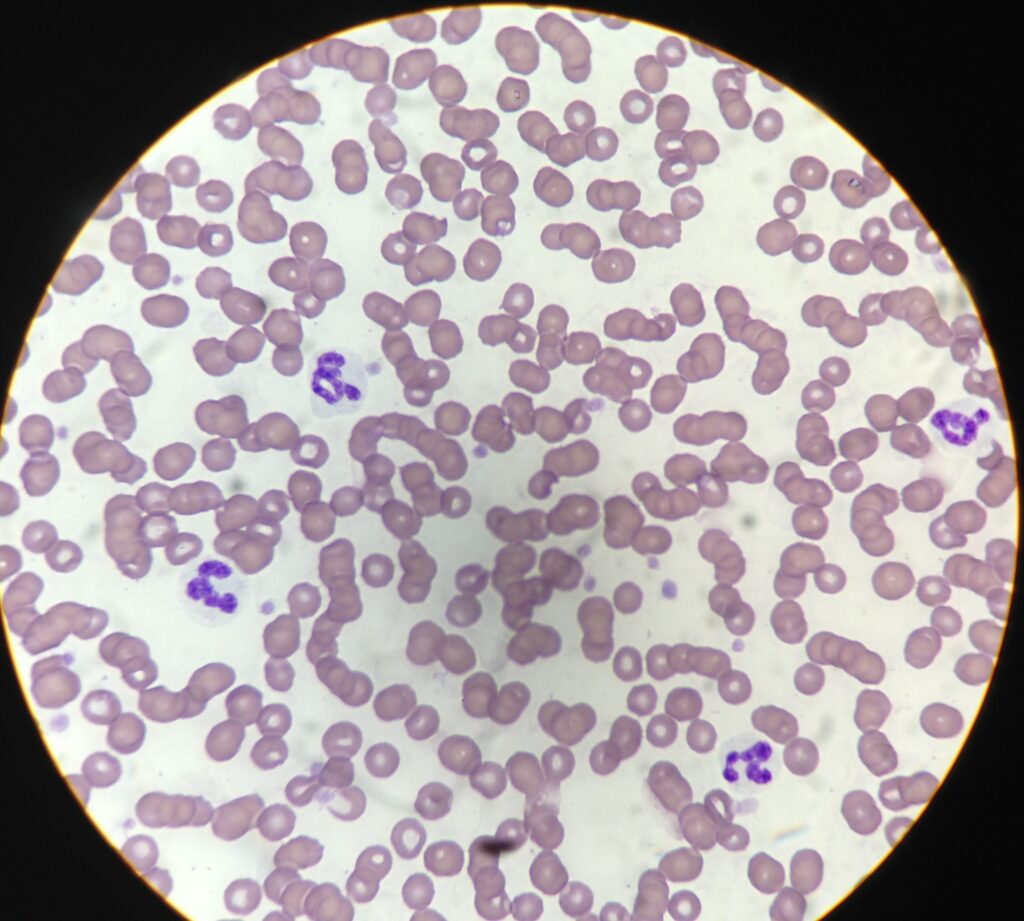

A single drop of the blood, the clinician should also make a simple blood smear. This is evaluated for the presence of spherocytosis, anisocytosis, and polychromasia, classically seen with IMHA. The blood smear should also evaluate the presence and appearance of white blood cells as well as platelets. Ideally, there should be 10-15 platelets per 100x oil high power field (as each platelet = 12,000-15,000 platelets).

Following the initial database, further diagnostics should be considered:

- Complete blood count and pathology review. Aside from anemia, spherocytosis, polychromasia, and anisocytosis, the CBC should also be evaluated for reticulocytes. A reticulocyte count is often greater than 80 x 103 /uL, or a corrected reticulocyte percentage > 1% is often found to be consistent with appropriate regeneration. It is important to keep in mind that dogs typically take 3–5 days to mount a regenerative response and a nonregenerative anemia can be seen in up to 50% of dogs at the time of presentation. Cats may appear non regenerative for an even longer period of time as they can take 7 days or more to mount a regenerative response.

- Serum biochemical abnormalities commonly include total bilirubin elevation, liver value elevations (ALT, ALKP), azotemia, hyperglobulinemia.

- Urinalysis – while a cystocentesis is ideal, this should not be performed prior to assessment of the platelet status, as certain patients may exhibit both IMHA and ITP concurrently. Once obtained, a urinalysis shows bilirubinuria or hemoglobinuria.

- Prolonged coagulation times (prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time) and increased fibrin degradation products and d-dimers are consistent with disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC).

While there is no one specific test to diagnose IMHA, IMHA is determined utilizing a combination of consistent clinical signs and diagnostic test results in an individual patient. Primary IMHA is a diagnosis of exclusion, and the patient should be evaluated carefully for causes of secondary IMHA or other reasons for hemolysis and anemia.

Additional diagnostics to consider include:

- Tick Titers (i.e. Lyme, Ehrlichia canis, Anaplasma, etc.)

- Coagulation panel

- Full body radiographs (as part of a neoplasia evaluation)

- Abdominal ultrasound (metastasis evaluation)

- +/- Lymph node aspirate

- +/- Coombs test

CLIENT COMMUNICATION

Once this diagnosis is made, it is important to discuss the findings with the owners as this is a long term (6 months), if not lifelong disease for many patients. While the long-term medications may be inexpensive, the short-term testing and treatment can be costly. Moreover, there are notable side effects of the disease and medications (i.e., pu/pd, polyphagia, hypercoagulability and predisposition to clot formation). From clinical experience as well as review of the literature, approximately 65-75% of these patients are discharged from the hospital, while approximately 30% of the patients do not survive to discharge or pass away within 1 year of diagnosis.

TREATMENT FOR IMHA

There is no single best treatment for patients with IMHA. Therapy consists of a combination of appropriate supportive care and immunosuppressive drug therapy. Therapies may include:

- Intravenous fluids

- Oxygen supplementation

- Transfusion therapy (packed red blood cell, whole blood)

- Gastrointestinal support

- To reduce the side effect of therapies such as corticosteroids.

- Immunosuppressive therapy

- Prednisone (1–2 mg/kg orally q12h)

- Azathioprine (2 mg/kg orally q24h

- Cyclosporine (see information below)

- Human intravenous immunoglobulin (hIVIG) can be considered in dogs refractory to other immunosuppressive therapies, dosed from 0.5–1.5 g/kg intravenously over 6–12 hours.

- hIVIG is believed to inhibit macrophage phagocytosis of red blood cells.

PROGNOSIS

Studies suggest 50–80% of dogs with IMHA will survive to discharge from the hospital. In the author’s experience, the patients that survive the initial treatment, the first 1-2 weeks, are more likely to do well and the patients that have complications or lack of response in this time are more likely to be in the category of non-survivors. Unfortunately, even in the patients that respond to initial treatment, relapses can occur. In the patients that do not survive, negative prognostic indicators include non-responsive autoagglutination, thrombocytopenia, hemoglobinemia and hyperbilirubinemia.

SUMMARY

Anemia is a complicated, yet potentially simple diagnosis when a practical, stepwise approach is considered.

References (For Part 1 and 2):

- Aronsohn MG, Dubiel B, Roberts B, Powers BE.Prognosis for Acute Nontraumatic Hemoperitoneum in the Dog: A Retrospective Analysis of 60 Cases (2003–2006). Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2009 March/April; 45:72-77.

- Brockman DJ, Mongil CM, Aronson LR, Brown DC.A practical approach to hemoperitoneum in the dog and cat. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000 May; 30(3):657-68. Review.

- Clifford CA, Pretorius S, Weisse C,et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of focal splenic and hepatic lesions in the dog. J Vet Intern Med 2004;18:330–338

- Croce MA, Fabian TC,et al. Presley Regional Trauma Center, Department of Surgery, University of Tennessee-Memphis, USA. Nonoperative management of blunt hepatic trauma is the treatment of choice for hemodynamically stable patients. Results of a prospective trial. Ann Surg. 1995 Jun; 221(6):744-53; discussion 753-5.

- Delgado Millán MA, Deballon PO. Department of Surgery, Hospital Universitario de Getafe, Spain. Computed tomography, angiography, and endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in the nonoperative management of hepatic and splenic trauma. World J Surg. 2001 Nov; 25(11):1397-402.

- Feldman BF, Zinkl JG, Jain NC, eds.Schalm’s Veterinary Hematology. 5th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2000.

- Hammer AS, Couto CG, Swardson C, Getzy D. (1991),J Vet Intern Med, Vol.5, No. 1, pp. 11-14.

- Hammond TN, Pesillo-Crosby SA.Prevalence of hemangiosarcoma in anemic dogs with a splenic mass and hemoperitoneum requiring a transfusion: 71 cases (2003-2005). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008 Feb 15; 232(4):553-8. Erratum in: J Am Vet Med.

- Hargis AM, Feldman BF. (1991),JAVMA, Vol. 198, No. 5, March, pp. 891-894.

- Herold LV, Devey JJ, Kirby R, Rudloff E. Clinical management of hemoperitoneum in dogs.J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2008;18(1):40–53.

- Hopper K, Bateman. An updated view of hemostasis: mechanisms of hemostatic dysfunction associated with sepsis.J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2005; 15(2): 83-91

- Levinson JG, Bouma JL, Althouse GC, Rieser TM.Prevalence of malignancy when solitary versus multiple lesions are detected during abdominal ultrasonographic examination of dogs with spontaneous hemoperitoneum: 31 cases (2003-2008). J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2009 Oct; 19(5):496-500.

- Millis DL, Hauptman JG, Fulton RB. (1993),Vet Surg, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 93-97.

- Mongil CM, Drobatz KJ, Hendricks JC. University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.Traumatic hemoperitoneum in 28 cases: a retrospective review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1995 May-Jun; 31(3):217-22.

- Nakamura K, Sasaki K, Murakami M,et al. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography for characterization of focal splenic lesions in dogs. J Vet Intern Med 2010;24:1290–1297.

- Pintar J, Breitschwerdt EB, Hardie EM, Spaulding KA.Acute Nontraumatic Hemoabdomen in the Dog: A Retrospective Analysis of 39 Cases (1987–2001). Am. Anim. Hosp. Assoc. 2003 November/December; 39:518-522.

- Scott-Moncreiff JC, Treadwell NG, McCullough SM, Brooks MB. (2001),JAAHA, Vol. 37, pp. 220-227.

- Smith SA, The cell based model of coagulation.J Vet Emerg Crit Care 19(1) 2009: 9-10

- Sorenson SR, Rozanski EA, Tidwell AS,et al. Evaluation of a focused assessment with sonography for trauma protocol to detect free abdominal fluid in dogs involved in motor vehicle accidents. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004;225:1198–1204.

- Streeter EM, Rozanski EA, de Laforcade-Buress A, Freeman LM, Rush JE. Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, Tufts University, North Grafton, MA.Evaluation of vehicular trauma in dogs: 239 cases (January-December 2001). J Am Vet Med Assoc. August 2009; 235(4):405-8.

- Thrall MA,et al. Veterinary Hematology and Clinical Chemistry. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

Only VETgirl members can leave comments. Sign In or Join VETgirl now!